Tragedy to triumph: how the adversities of boxing’s biggest underdog led to extraordinary success

Guest Written by Brandon Wright, MSc Sport and Exercise Psychology Student at Loughborough University.

The aims of this blog are:

To introduce the concept of later life adversarial growth within sport

Demonstrate using Buster Douglas how growth can be achieved following adversity

To introduce the Janus-faced model of adversarial growth

“On February 11, 1990, 1 minute and 23 seconds into the tenth round of a scheduled 12-round heavyweight championship fight, a fight NO ONE predicted would go beyond two rounds, James “Buster” Douglas knocked out Mike Tyson the heavyweight champion of the world. Tyson was 37-0 and was standing on the edge of immortality” [1].

Mike Tyson’s fight with Buster Douglas has gone down in history as one of the biggest upsets in professional sport. As Tyson was such a favourite to win, the fight was held in Japan because not enough people in the US would pay to see such a one-sided fight. All casinos but one wouldn’t allow bets on the fight as they thought there was only one possible result. The one casino that did allow bets gave Douglas 42-to-1 odds; the greatest ever odds in boxing, with the previous highest odds being only 10-to-1 in 1935.

23 days before the fight Buster received news that his mother had passed. For many this would result in worse performance and is statistically linked to negative outcomes. However, Buster experienced a transitional process where he gained new psychosocial and non-psychosocial resources, resulting in superior performance [2]. Some even speculated that this adversity is the reason for the biggest upset in boxing [1]. To understand how Buster dealt with this challenge and achieve adversarial growth, it is important to understand what adversarial growth is and the different ways adversity can be dealt with.

What are adversity and adversarial growth?

Adversities are “negative life circumstances that are known to be statistically associated with adjustment difficulties” [3]. Some adversities include the experience of trauma, tragic events, injury and death to name a few [4]. It is also important to note that the perception of adversity is subjective; a broken wrist to a nonathlete is likely to be an inconvenience, however a broken wrist to an Olympic boxer is likely to be an adversity.

Adversarial growth is when an individual faces a significant hardship which has the potential to result in positive changes such as superior performance due to an acquisition of psychological and psychosocial skills compared to the same individual before the adversity [5,6].

Research has shown that all of the highest-level elite athletes have faced some form of adversity such as trauma. Adversity can be experienced in both childhood and later life. However, both have shown to be to be a contributing factor for achieving the highest levels of performance when all things are equal [7]. This has been acknowledged by some Olympic athletes attributing their success to their experience of adversities [8]. Some researchers have said on average adversities are experienced around 16 years old, with memorability and awareness being contributing factors as to whether an event is interpreted as an adversity [9].

“To date, there is no evidence of any Olympic champions who have not experienced some adversity and trauma at some point in their lives.” [2]

This quote explains that experiences of adversity are seen as essential for success in the highest level of sport. By going through adversity, the experiences and skills gained can help with coping and the ability to overcome future adversity which can be the difference between winning and losing [8].

How do athletes grow following adversity?

The Janus-faced model of growth theorises following adversity an individual can react with a process of illusory growth and or constructive growth [10]. Illusory growth is associated with using maladaptive coping mechanisms to protect the individual from experiencing the true effects of the adversity but it is often used as a short-term fix. Whereas, constructive growth is associated with more adaptive handling of adversity. The process of adversity-related growth usually starts with components of illusory growth and as time passes individuals tend to use more constructive growth processes [11]

Illusory growth:

Denial – Short-term coping strategy whereby individuals fail to acknowledge the magnitude of their situation. This is for the protection of self-esteem by not attending to the negative emotions associated with experiencing adversity.

Seek meaning – When experiencing adversity, it is common to fixate on why this has happened rather than understanding the impact of the event itself.

Derogation of experience – Under-appreciating and under acknowledging the situation to create the impression that belittles the adversity experienced.

Assimilation – Through the use of manipulating cognitions e.g. unrealistic optimism, this creates a forced positive outlook to conform with pre-existing beliefs known as assimilation.

Constructive growth:

Accept adversity – This occurs when the individual has stopped denial and self-deception. The person begins to disclose their adversity to get support from their social network. This social support is key for facilitating growth following adversity.

Enduring distress – This differs from illusionary growth as an individual accepts and acknowledges that they are facing adversity rather than deceiving themselves into thinking everything is okay. This is advantageous as acknowledging the impact of adversity can result in making genuine changes.

Find meaning – Dedicating time to not only acknowledge the impact adversity had but to make sense of it and process this information.

Philosophical changes – Adversities often cause profound change such as a greater appreciation for life, change of perspective and enhanced relationships.

Accommodation – Cognitions are processed instead of manipulated. This means that following adversity these experiences are used to create new beliefs and schema. The ‘shattering of the self’ is rebuilt with this new information.

So, what can Buster Douglas teach us about adversity and growth?

The short interview above gives insight into the different facets of constructive growth Buster went through. 23 days before Buster Douglas’ world heavyweight title fight his mother passed away. This caused a shattering of his schema, beliefs and caused his life to be in disarray. Buster followed a path of constructive growth whereby he went through a transformational process. The adversity allowed for gaining new insights and resources which were used to “tap into his talent” leading to superior performance. This adversity can be seen to fuel his motivation as it goes from a want to win to an extreme need to win. Buster says following the passing of his mother he was even more confident going into the fight [6]. From the interview you can see there is constructive growth and minimal illusory growth such as denial, derogation of the adversity or fixation on seeking meaning. It can be seen that the experience of Buster’s trauma has facilitated the growth of new psychological mechanisms while also improving his existing psychological mechanisms such as confidence [9].

How do you know when you have grown following adversity?

Three indicators have been used in the literature to show evidence of adversarial growth [11]. These are just a few examples that show the achievement of growth:

Intrapersonal indicators– Increased resilience, strength, motivation and personal development

Interpersonal indicators– Enhanced relationships and the ability to disclose

Physical indicators– Superior performance, strength and health

All of which were demonstrated by Buster Douglas, not only in the build-up to the fight but also within the fight.

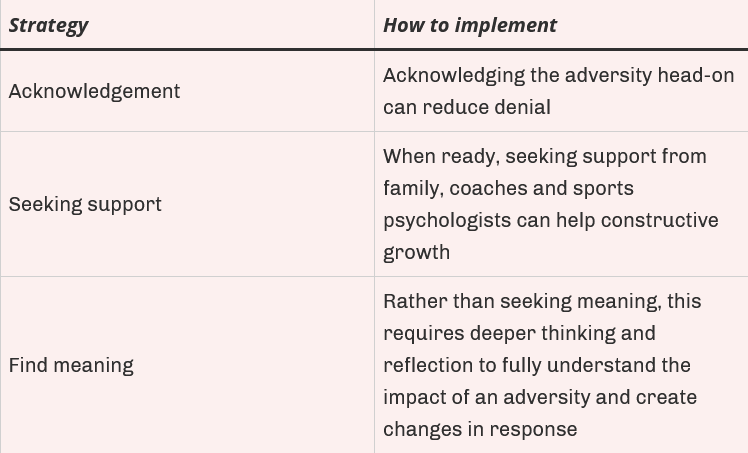

Strategies to promote constructive growth and transformational changes:

Take-home message

Adversities are inevitable and essential to reach the top. However, adversities on their own do not create success. Success is created by the changes an athlete makes in response to the adversity. Buster Douglas learnt from his adversity and implemented what he learnt to fuel his performance to beat an undefeated Mike Tyson, which was regarded by many as almost impossible.

References

Johnson, J., & Long, B. (2008). Tyson-Douglas: The Inside Story of the Upset of the Century. Potomac Books, Inc..

Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2017). Adversity-related experiences are essential for Olympic success: Additional evidence and considerations. In Progress in Brain Research(Vol. 232, pp. 159-165). Elsevier.

Luthar, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and psychopathology, 12(4), 857.

Jackson, D., Firtko, A., & Edenborough, M. (2007). Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: a literature review. Journal of advanced nursing, 60(1), 1-9.

Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of traumatic stress: official publication of the international society for traumatic stress studies, 17(1), 11-21.

Sarkar, M., Fletcher, D., & Brown, D. J. (2015). What doesn’t kill me…: Adversity-related experiences are vital in the development of superior Olympic performance. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(4), 475-479.

Hardy, L., Barlow, M., Evans, L., Rees, T., Woodman, T., & Warr, C. (2017). Great British medalists: Psychosocial biographies of super-elite and elite athletes from Olympic sports. In Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 232, pp. 1-119). Elsevier.

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychology of sport and exercise, 13(5), 669-678.

Savage, J., Collins, D., & Cruickshank, A. (2017). Exploring traumas in the development of talent: what are they, what do they do, and what do they require?. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(1), 101-117.

Maercker, A., & Zoellner, T. (2004). The Janus face of self-perceived growth: Toward a two-component model of posttraumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 41-48.

Howells, K., & Fletcher, D. (2015). Sink or swim: Adversity-and growth-related experiences in Olympic swimming champions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 37-48.